What do a Midwestern punk queen from Ohio and a Beauty Queen from Chicagoland have in common? How would they intersect in a young man desperately trying to be better? Can combat boots and leather impact high heels and lace? Let’s talk about Chrissie Hynde and Lauren.

Before I had a vocabulary for feminism, before I understood power or permission or what it meant to take up space as a woman in a man’s world I had Chrissie Hynde.

She didn’t ask for the spotlight. She commanded it. When The Pretenders dropped their debut in 1980, she arrived fully formed: eyeliner smudged, guitar slung low, and lyrics that refused to play nice. “I’m special,” she sang in Brass in Pocket, and the way she said it (cool, offhand, knowing, confident) sounded like a challenge to everyone who ever told a girl to stay quiet.

Chrissie was the first rock frontwoman I saw who didn’t apologize for anything. She snarled and strummed. She leaned into femininity without softening her rage. Punk sounded like a prayer. And without using the word feminist in early interviews, she became one anyway. Her every lyric and every strut across the stage was a rebuke to the idea that rock was only for boys.

Critics and historians have said it more eloquently than I ever could: she “transcended gender without relinquishing her truth as a woman.” She brought “a defiant, determined, take-on-all-comers momentum” to a scene still ruled by men. She kicked through the smoke of ‘70s machismo and made room for something sharper, smarter, more real.

For someone like me, a teenage Gen X boy marinating in locker room jokes and Breakfast Club gender roles, Chrissie Hynde was a signal flare on MTV. She made me notice. Not just her, but the women around me. And more importantly: the way I listened to them.

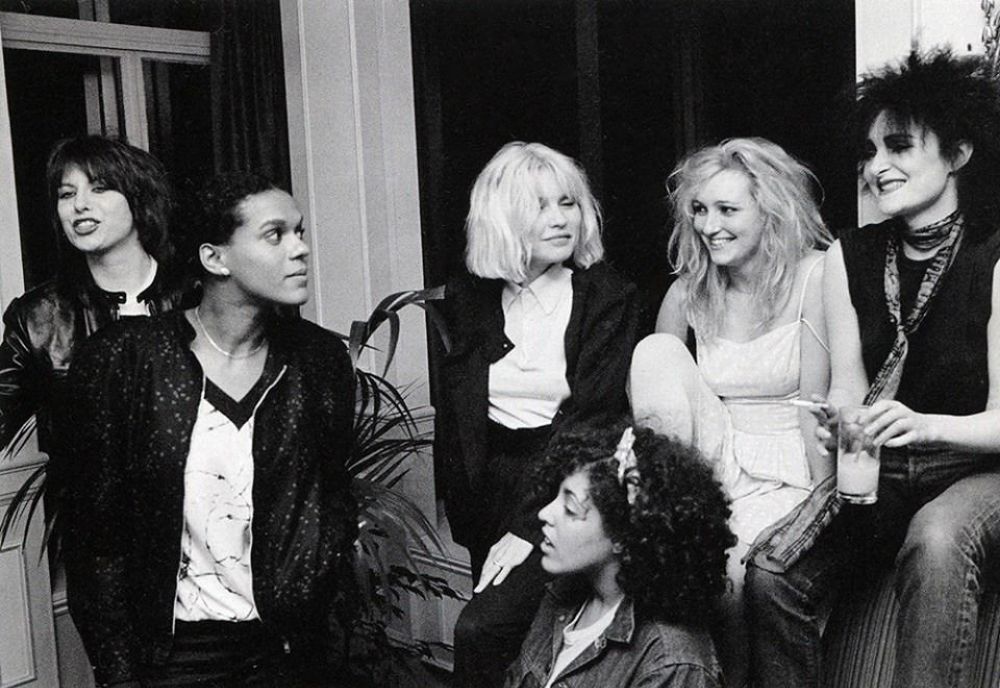

Punk Sisterhood and the Ladies’ Tea Party

Chrissie Hynde was part of a rising punk sisterhood that demanded space loudly, stylishly, and without apology. In time these pioneers would inspire the RIOTGRRL movement that would drive feminism foreword to the third wave.

I’ve written before about women like Debbie Harry and Joan Jett, those glorious rule-breakers who formed a kind of sonic resistance. Chrissie in many ways stood shoulder to shoulder, guitar in hand, boots on the floor, and sneer firmly intact with the spirit of Debbie and Joan.

There’s a famous photo I can’t get out of my head. It’s from a punk “Ladies’ Tea Party” held in London in the early ‘80s. As I wrote previously about it, it was an informal gathering of women like Debbie Harry, Siouxsie Sioux, Viv Albertine, Poly Styrene… and Chrissie Hynde. It wasn’t a protest. But it was a powerful moment that goes beyond the iconic photos. Just being in the room together was proof a disruption was underway.

I think about that image a lot. The eyeliner. The leather. The solidarity.

These women weren’t asking for entry into the boys’ club. They were building their own clubhouse while taking the stage and selling records.

Chrissie, by her own admission, didn’t always claim the feminist label. She shrugged it off in interviews. But there’s a deeper truth: she didn’t have to say it. Her presence was the proof. Every time she took the mic, she was rewriting the rules. With nine top 40 hits, three platinum albums, five gold albums, and four Grammy nominations she had nothing to prove to anyone.

The other women knew it. Joan Jett once said she loved Chrissie’s “frustration at not being taken seriously.” Viv Albertine called her “too talented for anyone to handle.” And Debbie Harry didn’t compete, she invited her in despite the record industry and radio industry always trying to pit female artists against one another. (Madonna vs Cyndi Lauper, The Go-Go’s vs the Bangles, and many other “fueds” were fabrications of the industry, not a reality).

There’s something sacred about that kind of solidarity. Something punk as hell. Something I didn’t recognize at 15, but I’m in awe of now.

The Girl They Called a Princess

For all the ways Chrissie Hynde transformed music, her impact hit me hardest when it reached someone I loved.

We’ll call her Lauren.

She was the kind of beautiful that made people forget she was human. She had the “it” factor with features that would’ve looked right at home in a Calvin Klein ad. She was already doing local modeling gigs by 16 (which is how I met her before I met her in HS theatre). But the spotlight she stepped into was cold, and it cast long shadows.

At school, the boys obsessed over her. The girls? They weaponized every ounce of their insecurity and aimed it straight at her heart.

“She thinks she’s better than us.”

“She’s stuck-up.”

“Too pretty to talk to anyone but herself.”

None of it was true.

Lauren wasn’t a snob. But she was starving. Not for attention or approval. Not for control. She was starving for a world that would let her exist in her body and self without commentary. She was also starving to stay in the brutal world that was modeling and pageants in the 80s.

Lauren had an eating disorder. No one knew how to talk about it back then, least of all teenagers in a Midwest high school where mental health was a fucking punchline and compassion was rare, even in theatre and band. I knew she picked at lettuce every day in the cafeteria, smiled like it didn’t matter, then nearly faint in gym two periods later.

She collapsed once. And still, the whispers didn’t stop. They pumped on the volume of gossip and shame without mercy or compassion.

When she was finally hospitalized for malnutrition, you’d think it might’ve cracked the cruelty down. It didn’t. The girls got meaner.

“She’s doing it for attention.”

“She wants to be a victim.”

“What a drama queen.”

It broke her. I could see it. She came back quieter, thinner, and somehow more invisible than ever. One night, in the middle of a summer thunderstorm, she called me. Her voice was small.

“I don’t want to do this anymore,” she said. “Sometimes I think it’d be easier if I just disappeared.”

That’s the moment Chrissie Hynde saved her life.

I was a damn kid. I didn’t know what to do with someone saying that. So I told Lauren to come over. I didn’t ask, I just told her. She said no so I drove to her house and knocked on the door scared she might hurt herself. She laughed, shook her head, and got in the car calling me a stubborn ass.

We drove in my Monto Carlo (where do you think Ford got his in my book, Hearts of Glass Living in the Real World?), Windows down, rain on the windshield, the world feeling like it might actually split open. We didn’t talk, I just popped in a Pretenders mix tape I made. The voice behind dark eyeliner, combat boots, and a guitar strapped tight like armor moved the beauty queen.

Chrissy didn’t ask anyone to love her. She dared them not to.

When she sang “Middle of the Road,” Lauren lit up.

That night didn’t fix everything. Recovery isn’t linear. But something shifted.

Lauren came back bit by bit. She stopped trying to smile when it wasn’t real. And when one of the girls called her “a walking eating disorder,” Lauren looked her dead in the eye and said:

“You don’t get to write my story, bitch!”

I’ve carried that moment with me my whole life.

Chrissie didn’t know her. But she saw her. She saw every girl who was mocked for being “too much.” Every boy trying to be better and every kid caught between what they were told they were and who they were becoming was given a model for being.

She gave us a language for defiance.

And Lauren? She lived beyond that time. Not without pain. But she lived like a flame refusing to go out. And part of that fire came from a midwestern girl from Ohio that moved to the UK to become a woman who changed the world, from a woman who taught her how to be loud, how to be messy, and how to stay.

Legacy and What We Still Need to Hear

Chrissie Hynde didn’t just change music singlehandedly, but she was part of a sisterhood that changed who got to make it.

Her refusal to conform cracked something open. Women who came after her in punk, indie, riot grrrl, or alt-pop, and even country. She walked through the door she pried loose with her boot. You don’t get Sleater-Kinney without Chrissie. You don’t get Garbage or Bikini Kill or Florence Welch without someone saying first, “You don’t need to sing pretty to be heard.”

Critics today still marvel at her balance of “strength, toughness, and vulnerability.” She showed that being a woman in rock didn’t mean trading femininity for power, rather, it meant defining both on your own terms.

She gave voice to those who weren’t given space. And she did it without a marketing team or a manifesto. She just did it.

Now, I’m in my fifties, and I look around at a world where women are still fighting and still having to justify their bodies, their choices, and their voices. I see old men in new suits trying to legislate control over people they don’t understand. I see girls like Lauren, every day, online and offline, being broken down by a culture still addicted to cruelty.

And I think about Chrissie. Still touring. Still growling. Still not asking for your damn permission.

She taught me how to listen. To be the kind of friend who doesn’t flinch when someone is in pain. The kind of partner who doesn’t assume what love is supposed to look like. The kind of man who believes women when they speak.

She didn’t teach me to save anyone in her lyrics. She taught me to stand beside them and know they are special eactly how they are

I hear her in the back of my mind, even now, like a riff on repeat:

Don’t shrink. Don’t apologize. Don’t disappear.

I think we still need Chrissie Hynde.

I think we always will.

Pat Green is the editor of GenXWatch.com and the author of “Hearts of Glass Living in the Real World,” a novel about trauma, found family, and refusing to give up. Get your copy of the book today in paperback or ebook (on sale now for $1.99).

Leave a Reply